Let me start this discussion by asking a question,

the same kind of question that Jesus asked about the baptism of John: Mark 11:30 The

baptism of John, was it from heaven, or of men? answer me. Now let us ask the question: The class room arrangement for teaching, is

it from God, or did it come as a invention of men?

First let us consider a generic command to go

teach. Mat. 28:18-20 And Jesus came

and spake unto them, saying, All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth.

19 Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of

the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost: 20 Teaching them to

observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you: and, lo, I am with you

alway, even unto the end of the world. Amen.

This is a generic command. We are told to go teach. The command for communion is also a generic

command. We are instructed to have the

communion but are not told how often. 1 Cor. 11:26 For as often as ye eat this bread, and

drink this cup, ye do shew the Lord's death till he come. However, we have

an example as to how often we are to have the communion service. This example is found in Acts 20:7, And upon the

first day of the week, when the disciples came together to break bread, Paul

preached unto them, ready to depart on the morrow; and continued his speech

until midnight. We understand that when we have an example

relating to a generic command, that example becomes binding as is with how

often we should have communion. In

reference to the generic command to go teach, we have an example in Acts 20:20,

And how I kept back nothing that was

profitable unto you, but have shewed you, and have taught you publickly, and

from house to house. Since we have this holy example given by the

apostle Paul, we understand that teaching is either done publicly or

privately. When it is done privately,

it is done by individuals or house to house, individually. The church as a body (collectively) has nothing

to do with it. We find examples of this

taking place in the book of Acts, (Acts 18:26, Acts

21:8-9).

As we examine the Sunday School or Bible Class that

many churches have, we see that they are clearly more public than private. The leadership of the Church decides that

they will have them. They decide who is

to do the teaching. Also, this work is

financed by the Church just like a gospel meeting. The whole congregation is expected to attend, that is, in their

perspective places. The public is

invited through signs and announcements, just as with a gospel meeting, however, women are allowed to teach, in different

capacity depending on the congregation and its leadership. In the individual capacity, the leadership

of the Church has nothing to do with where a person goes or whom they teach. In Acts 18 and Acts 21, they were teaching

in the individual realm (house to house).

The Church as a body had nothing to do with it. In Titus we find that the aged women are to

teach the younger women. Since women

are forbidden to do this in a public way, then it must be done privately, or as

individuals. Notice what they are

instructed to teach, Titus 2:2 That the aged men be sober, grave, temperate, sound in

faith, in charity, in patience. 3 The

aged women likewise, that they be in behaviour as becometh holiness, not false

accusers, not given to much wine, teachers of good things; 4 That they may teach the young women to be

sober, to love their husbands, to love their children, 5 To be discreet, chaste, keepers at home,

good, obedient to their own husbands, that the word of God be not

blasphemed. 6 Young men likewise

exhort to be sober minded. 7 In

all things shewing thyself a pattern of good works: in doctrine shewing

uncorruptness, gravity, sincerity, 8

Sound speech, that cannot be condemned; that he that is of the contrary part

may be ashamed, having no evil thing to say of you. These are things we are to teach with

our example of life, as well as privately, and publicly. What he is not instructing Titus to do is to

divide into groups and teach them separately.

Now as far as children are concerned, parents need to be present when

their children are taught. They need to

know what their children are taught.

Certainly there are things that women need to teach that do not need to

be taught in the presence of men, and likewise with the men. These things are better taught

privately. Paul made a point that he

taught “house to house” or privately and publicly.

Now let us consider "necessary

inference." We are commanded to

meet, therefore we must have some place to meet. It can be a house or a larger building. We have examples of both.

There is no necessary inference for the bible classes which divide into

little groups to teach. There is not

one passage that even hints that the Church in the first century had such

meetings. We can teach without

them! They are not necessary to

teach. Some say that they are necessary

for children to learn. They say that

children cannot be taught as they should in the general assembly. This in fact contradicts what God has

said. Consider Deuteronomy 31:12-13

and Deuteronomy 32:1-2. Deut. 31:12 Gather the people together, men, and women, and

children, and thy stranger that is within thy gates, that they may hear, and

that they may learn, and fear the LORD your God, and observe to do all the

words of this law: 13 And that their

children, which have not known any thing, may hear, and learn to fear the LORD

your God, as long as ye live in the land whither ye go over Jordan to possess

it. God said that the

children can learn in an audience with adults and parents. Deut. 32:1 Give

ear, O ye heavens, and I will speak; and hear, O earth, the words of my

mouth. 2 My doctrine shall drop as the

rain, my speech shall distil as the dew, as the small rain upon the tender

herb, and as the showers upon the grass:

3 Because I will publish the name of the LORD: ascribe ye greatness unto

our God. 4 He is the Rock, his work is

perfect: for all his ways are judgment: a God of truth and without iniquity,

just and right is he. Notice

how the rain falls. It falls on the

large mature oak tree as well as the tender baby oak tree. It falls on both alike and each absorbs what

it needs for growth. God’s word, works

the same way. It is taught to all and

each one absorbs what it needs to sustain life and to grow. As one grows it is able to understand more

and more. There is no inference for the

classes, neither is the class arrangement necessary for us to teach.

Let us consider what was commanded about public

teaching. 1 Cor. 14:31 For ye may all prophesy one

by one, that all may learn, and all may be comforted. This passage says all may teach or prophesy

in turn. This would be all who do

prophesy or have a desire to speak in the assembly may do so, one at a time. What I want you to notice is “all may

learn” and “all may be comforted”.

For all to learn and for all to be comforted, then all must be in the

room with the one who is teaching and all must hear what the one has

spoken. When we are in different rooms

being taught by different people, all do not learn nor are all comforted by

what any one person is teaching. Also

the commandment says the women are to be silent. They are commanded not to speak. They cannot be a speaker in

church assemblies. 1 Cor. 14:34 Let your women keep silence in the

churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to

be under obedience, as also saith the law.

35 And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at

home: for it is a shame for women to speak in the church. This passage is teaching the

same thing as does 1 Timothy 2:11-12 Let the woman learn in silence with all

subjection. 12 But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority

over the man, but to be in silence. These two passages teach basically the same thing. That is that women are to be silent in

church meetings. The commandment for

public teaching of the church is that the men may teach one at a time and the

women are silent.

Some say that 1 Corinthians 14:34 is speaking of the

prophet's wives and does not apply to us today because we do not have inspired

prophets. Inspired or not, he is giving

regulations for teaching. They use this

same chapter to regulate the use of tongues.

Also notice, if it was only speaking to the wives of the prophets then a

young woman who was not married could teach.

Certainly this is not the case.

When he says let them ask their husbands at home, he is speaking of the

realm of the individual, like the “house to house” (Acts 20:20) that Paul spoke

of, or like “what have ye not houses to eat in” (1 Cor.11:22), or “eat at home”

(1 Cor. 11:34). By these statements he

is speaking of the realm of the individual or private. Certainly he does not mean that we have to

be in our house to eat. Neither does a

woman have to have a husband to ask a question. She is to ask privately and not in church meetings. Notice he said, “it is a shame for a

woman to speak in the church”. This

does not apply to singing. Singing is

not the same thing as taking the leadership in teaching others. As this chapter is dealing with speaking in

the church for edification and instruction, the woman cannot take a spot in the

pulpit nor lead the singing, but she is to sing as she is commanded to.

Still some will say that 1 Corinthians chapter 14

only deals with worship. By this they

mean that it only pertains to the assembly where communion is served. The bible does not say this. They bring up 5 elements of worship,

however, we worship God daily in many different aspects. The wise men worshipped and they certainly

did not have 5 elements there (Mat. 2:11).

But when these speak of this worship, they have reference to the

assembly when communion is taken.

Certainly at this time there is teaching, praying, singing, and a

collection is taken up (Acts 20:7; 1 Cor. 16:1-2), however, the church in the

first century had meetings for other reasons also, (Acts 15). The context of 1 Corinthians 14 is teaching

or edifying in a church gathering. 1 Cor. 14:3 But he that prophesieth speaketh unto men

to edification, and exhortation, and comfort; 1 Cor. 14:26 How is it then,

brethren? when ye come together, every one of you hath a psalm, hath a

doctrine, hath a tongue, hath a revelation, hath an interpretation. Let all

things be done unto edifying. While

this chapter deals with tongues, teaching, and singing, it does not deal with

communion nor giving. It seems to me

that it would apply when any of these things are being done by the body, the

church. 1 Cor. 14:15 What is it then?

I will pray with the spirit, and I will pray with the understanding also: I

will sing with the spirit, and I will sing with the understanding also. Certainly one could not be right by

singing praying, or teaching in a tongue that he does not understand. This chapter must apply to any gathering

where teaching is taking place.

Now one advocate of the classroom arrangement for

teaching said, “we practice I Cor. 14:31.

In each of the classes has only one person speaking at a time and all

hear what the one says”. But you see he

could not nor would he have communion in each of those classes. Neither does he follow the rest of I Cor.

14, because they have women speaking or teaching some of the classes. You see the classes are public, and if not,

then the women could teach anyone, but they divide the congregation, and that

is why they could not have communion in them.

Furthermore, if they had communion in them, each would be a separate

congregation. If each is a separate

congregation, then it should have all kinds of people in it and should have one

teacher at a time and the women should be silent.

A church paper published an article which said that in Acts 2 they had to have

classes. They reasoned that since 3,000

were baptized in one day, they could not get all in one room, but they did have

large meeting places in Jerusalem, as well as other Roman Cities in those

days. If they did have to meet in

different places, buildings, or rooms, they would have met with men, women and

children in each of these meetings. If

they did such, each group would have been a separate congregation of the Lord’s

Church. Each congregation would also

have followed the instructions given in 1 Corinthians chapter 14. Those assemblies would not have been

anything like the bible classes or Sunday School which churches have today.

When do individual study groups cross over to be

public teaching? Suppose some men or

women, or both, decide to meet some friends at the church building to study some

subject in the bible, is that ok? Yes,

that is ok. However, when the church as

a body takes charge or takes the oversight of these who are meeting, then it

goes into the public realm of teaching.

They are no longer acting as individuals, but are a function of the

body, the Church. Thus they would come

under the regulations of 1 Corinthians 14.

The same line of argument which will not allow

instrumental music to be used in Church assemblies, would also close the door

on Bible Classes or Sunday School. Not

one passage or reference to them can be found in the New Testament, neither can

they be found in the Old Testament.

Thus an argument can be made from the silence of the scripture. The reason for this, is the fact that the 1st

century church did not have bible classes.

They are a modern addition.

The following are some things that I got off the

internet showing that the class arrangement of teaching was not in the 1st

century of the Church.

A Primitive Baptist Statement on Sunday School

Sunday School is a relatively late development in the history of the

Christian church. The first Sunday school was established by the English

Methodist Robert Raikes at the end of the 18th century. Sunday school

originally was intended as a means to reach the children of unbelieving

parents, not the children of church members. However, in the middle decades of

the 19th century a growing number of church members enrolled their children in

Sunday schools. Some Christians, especially Presbyterians and Baptists, were

not convinced of the Scriptural warrant for Sunday school in teaching the Bible

to the children of Christians. In 1832, a Reformed Baptist denomination, the

Primitive (in the sense of harkening back to "primitive" or early

Christianity) Baptists stated:

"Sunday schools claim the honor of converting their tens of

thousands; of leading the tender minds of children to the knowledge of

salvation, [just] as the preaching of the gospel [does] that of bringing adults

to the same knowledge, etc. Such arrogant pretensions, we feel bound to oppose.

First, because they are grounded upon the notion that conversion or

regeneration is produced by impressions made upon the natural mind by means of

religious sentiments instilled into it; and if the Holy Ghost is allowed to be

at all concerned in the thing, it is in a way which implies His being somehow

blended with the instruction, or necessarily attendant upon it; all of which we

know to be wrong.

"Secondly, because such schools were never established by the

apostles, nor commanded by Christ. There were children in the days of the

apostles. The apostles possessed as great desire for the salvation of souls, as

much love to the cause of Christ, and knew as well what God would own for

bringing persons to the knowledge of salvation, as any do at this day. We,

therefore must believe that if these schools were of God, we should find them

in the New Testament.

"The Scriptures enjoin upon parents to bring up their children in

the nurture and admonition of the Lord.

"But while we stand thus opposed to the plan and use of these Sunday

schools in every point, we wish to be distinctly understood that we consider

Sunday schools for the purpose of teaching poor children to read, whereby they

may be enabled to read the Scriptures for themselves, in neighborhoods where

there is occasion for them, and when properly conducted, without that

ostentation so commonly connected with them, to be useful and benevolent

institutions, worthy of the patronage of all the friends of civil liberty

(Cited in Mike Strevel. "Family Church," in Quit You Like Men,

October 1994. pp.11-12)."

Return to the Covenant Family Fellowship home page.

A Brief History of Biblical Family Worship

by Kerry Ptacek

[This is a slightly edited version of an article which appeared in the

November 1997 issue of Ligonier Ministries' Table Talk. Many of the documents

cited may be found at the Covenant Family Fellowship homepage.]

The distinctive elements of Biblical family worship, leadership by the

male head of the family and the use of God's word, are found throughout the

Bible, in the ancient Church, and in those churches which prepared and continue

the Reformation to this day.

[Biblical History]

God's plan for Abraham involved spiritual leadership in his household:

"For I have known him, in order that he may command his children and his

household after him, that they keep the way of the LORD, to do righteousness

and justice, that the LORD may bring to Abraham what He has spoken to him"

(Gen 18:19). Jacob recovered leadership in his household by emphasizing God's

word and worship in the family (Gen 31:4-16; 35:1-15).

The law required that the father answer questions posed by his children

on the meaning of the Passover, the firstborn and the covenant (Ex 12:1-28;

13:1-16). The responsibility of men to teach their families God's words

generally also was affirmed: "You shall teach them diligently to your

children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, when you walk by

the way, when you lie down, and when you rise up" (Dt 6:6-7; 11:18-19).

This spiritual role for fathers was understood in the time of David.

Asaph wrote of "sayings of old, which we have heard and known, and our

fathers have told us" and promised: "We will not hide them from their

children, telling the generation to come the praises of the LORD, and His

strength and His wonderful works that He has done. For He established a

testimony in Jacob, and appointed a law in Israel, which He commanded our

fathers, that they should make them known to their children" (Ps 78:1-6).

The spiritual leadership of the male family head continues in the New Testament.

The husband was to model the love of Christ in washing his wife "by the

word" (Eph 5:26). So, too, the fathers were commanded to "bring up

your children in the training and admonition of the Lord" (Eph 6:4).

[The Ancient Church]

Ignatius, who as a boy in Antioch saw Paul, said fathers should teach

their children the Bible. His contemporary, Clement of Rome (30-100) reminded

the Corinthians to teach their wives the Bible. Clement of Alexandria (153-217)

preached that the husband and wife should practice united prayer and Scripture

reading every morning. The North African elder Tertullian (142-220), in a book

dedicated to his wife, spoke of the spiritual unity of Christian marriage

through prayer, the word of God, and singing.

The Apostolic Constitutions (200-400) emphasized the need to examine a

candidate for the office of overseer as to "whether he hath a grave,

faithful wife, or has formerly had such a one; whether he hath educated his

children piously, and has 'brought them up in the nurture and admonition of the

Lord.'" The Apostolic Constitutions paraphrases Paul's command: "Ye

fathers, educate your children in the Lord, bring them up in the nurture and

admonition of the Lord."

John Chrysostom (347-407), Bishop of Constantinople, witnesses to the

continuation of the Biblical view in urging that every house should be a

church, and every head of a family a spiritual shepherd. However, in the

western church married men gradually were removed from church leadership by

canon law. Celibate clergy supplanted the father's role as a spiritual leader.

[The Reformation]

Through Waldensian Bible distribution and later the invention of the

printing press, Biblical family worship is reported again in European homes

before the Reformation. Handbooks for fathers and manuals for catechizing in

the home were produced. The earliest Protestant confession, the Bohemian,

included such a manual.

The revival of family worship became part of the Reformation's agenda of

restoring the life of the church on a Biblical basis. The practice especially

was developed among British Puritans and Presbyterians. Thomas Becon

(1512-1567), Thomas Cranmer's chaplain, said through a son being catechized by

his father: "Every man is a bishop in his own house. Who seeth not then

that the householder is bound to teach his household, the chief member whereof

the wife is, and therefore necessarily to be instructed and taught of her

husband?" In 1557 John Knox wrote to his congregation as he went into

exile: "you are bishops and kings; your wife, children, servants, and

family are your bishopric and charge. Of you it shall be required how carefully

and diligently you have instructed them in God's true knowledge... And

therefore I say, you must make them partakers in reading, exhorting, and in making

common prayers, which I would in every house were used once a day at

least."

[Puritanism]

This emphasis was carried to America. The first settlers of Salem entered

into a covenant in 1629 “Promising also unto our best ability to teach our

children and servants the knowledge of God, and of His Will, that they may

serve Him also.” Cotton Mather recounts many examples of prominent New

Englanders leading their households in family worship. With the rise of

Christian state education, family worship began to decline in New England at

the end of the 17th century.

In the Westminster Confession of Faith daily family worship is taken for

granted (XXI.VI). Thomas Manton's preface to the Confession spoke entirely of

its use by heads of families in the home. However, only a Directory for Public

Worship was adopted by the Assembly. The Church of Scotland fulfilled the

Assembly's intent in adopting a Directory for Family Worship in 1647.

English Puritanism after Westminster continued to emphasize the

distinctive features of Biblical spiritual leadership in the home. Richard

Baxter stated that "The husband must be the principal teacher of the

family. He must instruct them, and examine them, and rule them about matters of

God." Three decades later, Matthew Henry preached in his 1704 sermon

"On Family Religion" that "Masters of families, who preside in

the other affairs of the house, must go before their households in the things

of God. They must be as prophets, priests, and kings in their own families; and

as such they must keep up family-doctrine, family-worship, and

family-discipline..."

[18th & 19th Century America]

American Presbyterianism was shaped by The Directory for Family Worship,

which stated that family worship was necessary so that "the power and

practice of godliness, amongst all ministers and members of this kirk,

according to their several places and vocations, may be cherished and

advanced." In 1733 the Synod of Philadelphia, in seeking "some proper

means to revive the declining Power of Godliness," recommended "to

all our ministers and members to take particular Care about visiting families,

and press family and secret worship, according to the [W]estminster

Directory."

During the Great Awakening George Whitefield preached that "we must

forever despair of seeing a primitive spirit of piety revived in the world

until we are so happy as to see a revival of primitive family religion."

He reiterated that "every governor of a family... [is] bound to instruct

those under his charge in the knowledge of the Word of God." Jonathan

Edwards (1703-58) stated in his "Farewell Sermon" that "family

education and order are some of the chief means of grace. If these fail, all

other means are likely to prove ineffectual."

After Independence from Great Britain, all American Presbyterians adopted

some form of The Directory for Family Worship. Many Presbyterians shared the

view in the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Christian Magazine of the South, in

1845 that "Family Worship is one of [the] singular actions of God's people.

We do not look for this, we do not expect it, from those 'who are the enemies

of the cross of Christ.'" Failure to carry out family worship was treated

as a matter of church discipline: "by no means to admit either to the

table of the Lord, or to baptism for their children, any by whom it is

habitually neglected."

[The 20th Century]

Family worship began to decline even among Presbyterians from the middle

of the 19th century with the rise of Sunday school. Nevertheless, at the

beginning of this century the Southern Presbyterian General Assembly still

affirmed that "God requires in the home daily instruction of the children

in the Scriptures and the training of the children in all forms of Christian

service. God lays on the man, as the head of the family, the chief

responsibility for the performance of these requirements... and will not

sanction the delegation of this responsibility to the wife, the Sabbath school,

or to any other agency."

Family worship continued to be spoken of and advocated in some Presbyterian

denominations and groups such as the Family Altar League down to the middle

decades of this century. From the late 1980s a revived interest in Puritanism

and concern about the spiritual condition of Christian families have combined

in a renewed interest in Biblical family worship. Whether it is the Lord's will

that this be a time of Reformation, remains to be seen.

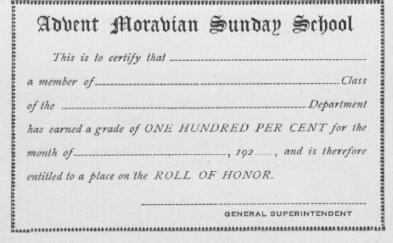

Material History of American Religion Project

Moravian Sunday School Certificates

The first Sunday schools predate the public school system. Christian

groups founded the schools to teach young workers to read; the school was held

on their only day off. By the late nineteenth century, however, public schools

had taken over the teaching of basic literacy. Moreover, they began to define

education in America. Soon Sunday schools began to copy the age-based class

structure, work requirements, and rewards of the public school.

These objects came from a Moravian Sunday school in Winston-Salem, North

Carolina, dating from the 1920s. They show how closely the school mimicked the

public schools. Note that class members received credit for bringing their

offering and Bible, being on time, and preparing their lesson. If they received

a top grade, they were added to the honor roll; if they failed to attend,

however, the teacher lowered their grade. As the record card shows, regular

attendance was very important.

The world's first Sunday Schools were

established in the 16th century. In the 1770s the Unitarian minister Theophilus

Lindsey provided free lessons on Sunday at his Essex Street Chapel in London.

However, it is Robert Raikes, the owner of the Gloucester

Journal who started a Sunday School at St. Mary le Crypt Church in

Gloucester, who usually gets the credit for starting the movement. Although not

the first person to organize a school in a church, Raikes was able to use his

position as a newspaper publisher to give maximum publicity for his educational

ideas.

The bishops of Chester and Salisbury gave support to Raikes and in 1875 a

London Society for the Establishment of Sunday Schools was established. In July

1784 John Wesley recorded in his journal that Sunday Schools were "springing

up everywhere". Two years later it was claimed by Samuel Glasse that there

were over 200,000 children in England attending Sunday schools.

In 1801 there were 2,290 Sunday schools and by 1851 this had grown to 23,135.

It was estimated that by the middle of the 19th century, around two-thirds of

all working class children aged between 5 and 15 were attending Sunday Schools.

***************************************************************************************************************************************************************

"REFLECTIONS"

by Al Maxey

Issue #184 -------

April 14, 2005

**************************

I verily think these Sunday

Schools are one of the noblest specimens of charity which have been set on foot

in England since William the Conqueror.

John

Wesley (1703-1791)

**************************

Raikes' Ragged Regiment

Reflecting on the Sunday School and

Non-Sunday School Movements

Sunday Schools have been around for so long, and have

become so much a part of most of our lives, that a great many of us may believe

they have just always been there! Have you ever wondered about the source of the Sunday

School? Who started it? And why?

The actual concept

of providing spiritual instruction for children and youth is nothing new.

Indeed, it's as ancient as mankind. Moses told the people of Israel,

"These words, which I am commanding you today, shall be on your heart; and

you shall teach them diligently to your sons and shall talk of them when you

sit in your house and when you walk by the way and when you lie down and when

you rise up" (Deut. 6:6-7). "The people were not to concern

themselves only with their own attitudes toward the Lord. They were to concern

themselves with impressing these attitudes on their children as well" (The Expositor's Bible Commentary,

vol. 3, p. 66).

The ancient Jewish historian Josephus, in his classic

work Antiquities of the

Jews, informs us that children were regularly instructed in

the Law of God beginning at a very early age. "Let the children also learn

the laws, as the first thing they are taught, which will be the very best thing

they can be taught, and will be the cause of their future felicity" (book

4, chapter 8, section 12). This early instruction of the young was so thorough

that Josephus observed, "If any one of us should be questioned concerning

the laws, he could much more easily repeat them all, than his own name."

Few people question the need for instruction of the young (or even of adults,

for that matter). The problem has always been associated with how, when, and by whom this instruction

should be accomplished.

The focus of this present issue of my Reflections, however, is the modern Sunday

School movement of which most of us are familiar, and in which most of us

probably participated as children, and with which we most likely still involve

ourselves at the present in some capacity. Although there is some debate as to

exactly when,

where,

and by whom

the first Sunday School was established, most attribute its development, if not

its origin, to a man by the name of Robert Raikes (1735-1811). He was born

September 14, 1735 in Gloucester, England, to Robert and Mary Raikes. He served

as an apprentice to his father, who was a printer and the founder of the Gloucester Journal. When

his father died in 1757, Raikes became editor of the paper, enlarging its size

and making significant improvements to the layout.

- Robert Raikes was a good

man and a beloved employer. A woman by the name of Fanny Burney described

him as "a good liberal master who paid good wages." Others

characterized him as "cheery, flamboyant and warm-hearted" (T.

Kelly, A History of Adult Education in Great Britain, p. 75). He

was also a very compassionate man, and a religious man. He loved people

and he loved his community, seeking to ennoble and enrich the lives of

both. Raikes was also passionate about the need for prison reform,

deploring the conditions of the British penal system, feeling it did more

harm than good. He spent a lot of time visiting the prisons, and then used

the Gloucester Journal to inform the public of the horrendous

conditions he observed therein.

One of the concerns Raikes had was over the plight of the poorer children

of his city. He observed how easy it was for them to drift into a life of

crime, and thus end up in the prison system. It was his conviction that a great

many of the parents of these poor children -- children who were spending a lot

of time on the streets while the parents were working in the factories (and

oftentimes the children themselves were forced to work in the factories) --

were "totally abandoned themselves, having no idea of instilling into the

minds of their children principles to which they themselves were entire

strangers." If these parents were neglecting their obligation to teach

their children, and to pass on to them good moral qualities, then Raikes felt another means of doing so

must be found. Robert Raikes had once commented, "The world marches forth

on the feet of little children." Thus, he believed very strongly that if

one sought to change society for the better, and ultimately decrease the prison

population, one must reach the children.

The children of the poor were in particular need of help, as they often

had to work in the factories six days a week to help support their parents.

Thus, they were uneducated, with little prospect for bettering themselves as

they grew older. They were poorly dressed, ragged, unwashed, and often hungry

and sickly. Sunday was the only day they had free, and many of these children

would roam the streets on Sunday, making a lot of noise and getting into all

kinds of mischief. There were often complaints from the "good church

folk" that on Sunday, as they were attempting to worship, "the street

was full of children cursing and swearing and spending their time in noise and

riot."

To help solve this problem, Robert Raikes, along with a local pastor

named Thomas Stock, decided to start a Sunday School at St. Mary le Crypt Church

in Gloucester. This was July, 1780. He hired four local women to serve as

teachers, and began to put the word out through his newspaper. In rather short

order they were able to enroll about 100 children, ranging in age from five to

fourteen years old. Some of the children were reluctant to come at first; they

were embarrassed because their clothes were so torn and ragged. However, Raikes

told them that all they needed was "a clean face and combed hair."

Every Sunday the school provided reading lessons from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. (with

an hour in the middle for lunch, which was provided). They were then taken to

the church and instructed in the catechism until about 5:30 p.m. Raikes also

printed up the reading and study materials, providing them to the children at

no cost. He proved to be quite a generous benefactor to the poor children of

his city.

- There were a great many

people in the city, however, who thought it was a complete waste of time

for Raikes to attempt to educate "the little savages," as they

called the children of the street. Even some of the officials in the

church would not back his efforts, suggesting his school dishonored the

Lord's Day. He and his Sunday School were derisively nicknamed "Bobby

Wildgoose and his Ragged Regiment." Others mocked him by speaking of

his "Ragamuffin Roundup." Robert Raikes was not easily

discouraged, however, and was all the more determined to try and make a

difference in the lives of these children, and also in the life of his

community.

In time, the transformation of these young people was dramatic. They ceased

their swearing and cursing, they began to behave responsibly, and developed a

desire to better themselves. A hemp and flax manufacturer in the city, a man by

the name of Mr. Church, who employed many of these children during the week,

said, "The change could not have been more extraordinary, in my opinion,

had they been transformed from the shape of wolves and tigers to that of

men." Society also benefited from this Sunday School. After Raikes began

this effort the crime rate dropped astoundingly both in the city and county

where Raikes lived. In fact, in 1786 the magistrates of the area passed a

unanimous vote of thanks

for the impact Robert Raikes and his Sunday School had upon the morals of the

youth of that area.

In 1785 a Sunday

School Society was formed in London for the purpose of

helping distribute Bibles and spelling books, as well as to help coordinate and

develop the work of this growing movement. By 1784, just four years after

Robert Raikes started his Sunday School with a hundred students in Gloucester,

there were said to be thousands

of students in Sunday Schools across England, with adults attending as well as

children. The movement grew impressively, and by 1851 it was reported that

three quarters of all working class children were attending such Sunday Schools

(T.W. Laqueur, Religion and

Respectability: Sunday Schools and Working Class Culture, p.

44). Just eight years after Raikes formed his first Sunday School, John Wesley

wrote to a friend, "I verily think these Sunday Schools are one of the

noblest specimens of charity which have been set on foot in England since

William the Conqueror."

Raikes himself, not one to seek personal acclaim for his efforts, gave

all the glory and praise for this work to the Lord God. He wrote,

"Providence was pleased to make me the instrument of introducing Sunday

School and regulations in prisons. Not unto us, O Lord, but unto Thy name be the

glory." Robert Raikes died of a heart attack in 1811. The local children

of the Sunday Schools attended his funeral, and each child, by prior order, was

given a shilling and a large piece of Raike's famous plum cake. Even in death

he was thinking of the children!

Expansion to America

As one might imagine, Sunday Schools became far too popular a concept to

remain only in England. The idea began to spread rapidly to other nations as

well. There is some argument as to exactly when and where the first Sunday

School was started in the American colonies. Some historical evidence exists to

suggest that Sunday instruction of children occurred as early as 1669 at the

Plymouth colony, and also at Roxbury, Massachusetts in 1674. In 1785 a Sunday

School was begun by William Elliott in Accomac County, Virginia. Each Sunday

afternoon Elliott arranged to have several white boys and girls meet in his

home to be instructed in the Bible. The Negro slaves were taught at a different

hour. A year later, in 1786, a second school was founded in Hanover County,

Virginia by a Methodist preacher named Francis Asbury. This Sunday School was

primarily concerned with the instruction of the Negro slaves.

Initially, both in Europe and America, the Sunday School was a private endeavor, largely

run by individuals who simply had an interest in the education, both spiritual

and secular, of the underprivileged children of the day. Soon, however, people

began to see the need for a more organized, united effort to spread this

concept throughout the land. Thus, with the dawning of the 19th century, more

and more Sunday Schools came to be established, organized and overseen by

various societies and unions. In other words, they came to be

institutionalized. The first one in America was formed in Philadelphia in

January, 1791. It was known as the "First

Day School Society," and was formed to provide for the

education of the poor female children of that city. Other large cities soon

followed the lead of Philadelphia, including Pittsburgh, Boston, New York,

Albany, Hartford, Baltimore, and Charleston.

The spirit of Nationalism contributed to a growing demand for a Sunday

School organization on a national

level. This perceived need led to the formation, in May, 1824, of the "American Sunday School Union."

Its purpose, as stated in its constitution, was: "To concentrate the

efforts of Sabbath School societies in different portions of our country; to

disseminate useful information; to circulate moral and religious publications

in every part of the land; and to endeavor to plant Sunday Schools wherever

there is a population." Six years later they decided to send missionaries

over the Alleghenies into the Mississippi Valley. Perhaps the best known of

these missionaries was a man by the name of Stephen Paxson. He traveled from

one small community to another, from the Alleghenies to the Rockies, all on his

horse, which he had named "Robert Raikes." During his many years of

service to the ASSU,

he established and organized 1314 Sunday Schools, with a total of 83,405

teachers and students. Many of these planted Sunday Schools eventually grew to

become churches

within the community in which they had been established. The churches then

typically retained the Sunday School as a part of their organization and

missionary outreach.

Eventually it was decided that National

Sunday School Conventions were needed, and that they should

be held annually. The first was held in Philadelphia in 1832. There were 220

delegates from 15 states present. Some of the topics discussed at this

convention were the need for organizing an Infant/Toddler program in the Sunday

Schools and the need for qualifying teachers. The second national convention

was held in 1833, also in the city of Philadelphia. The third convention was

again held in Philadelphia, but it was 26 years later, in 1859. Seventeen

states were represented, with one visitor from Great Britain. The fourth

national convention was held ten

years later, in 1869, in Newark, New Jersey. There were 526 delegates in

attendance, representing 28 states. Visitors from England, Canada, Ireland,

Scotland, and South Africa attended.

- The fifth convention was

held in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1872. This was a very important

convention because it was at this time that the International Uniform

Lesson was adopted. Up to this point there had been no common

curriculum for the Sunday Schools throughout the country. Each

denomination was preparing and providing its own lessons. Thus, a

committee was formed that would arrange for a uniform curriculum

to be shared by all. Some did not like this idea, however, and the International

Graded Series was created (also known as the Closely Graded

Lessons). This series provided a bit more variety. Others developed

the Group Graded Lessons (also known as the Departmental

Graded Lessons), which were designed to be age appropriate. Many

denominational groups in more recent times, however, are moving away from uniform

lesson materials and are returning to the previous independence

-- i.e.: each group independently determining for itself its own

curriculum based on its own needs.

From 1872 onward, the National

Sunday School Conventions have met every three years, and,

due to a large number of foreign nations participating in these conventions,

they have changed their name to the International

Sunday School Convention. Many religious education scholars,

as well as church history scholars, believe that the Sunday Schools did as much

to "tame the west" in the early days of our history as just about

anything else. It also had a tremendous impact on the spread of Christianity

westward. Although not everyone appreciated the concept of the Sunday School,

few would deny its impact upon society.

The Anti-Sunday School Movement

As might be expected with virtually any new concept or practice, there has

always been an element of fierce opposition to Sunday Schools running parallel

to this movement throughout history. Whereas some happily embraced the idea of

a Sunday School, and others were basically indifferent to it, some were vehemently

opposed to the whole concept. Indeed, there were a few radical opponents who

even went so far as to declare that anyone

who endorsed or participated in a Sunday School would go to hell. This

was not a minor issue to these people; it was not a matter of personal opinion.

It was a matter of FAITH, and heaven and hell rested in the balance!

In 1830, a Baptist

Association in the state of Illinois passed a resolution

which said, in part, "We as an Association do not hesitate to say that we

declare an unfellowship

with Foreign and Domestic Mission and Bible Societies, Sunday Schools, and all

other Missionary Institutions." A good many of the Baptist churches in the

Midwest at that time adopted this anti-mission society and anti-Sunday school

position. In the early 19th century in America, many "extra-church"

societies and institutions began forming. There were foreign missionary

societies, Bible societies, tract societies, temperance societies, anti-Masonic

societies, and countless others. Most all of these were operating outside of

the oversight of regular denominational groups. They had become independent

efforts to do the work of the Lord. This raised significant concerns in many of

the more fundamentalist groups -- a concern that the church was being

supplanted by a human institution. Therefore, these various efforts, among

which was the Sunday School, were perceived by some to be an attack against the

church itself, and thus the work of Satan.

Several denominational groups split over this Sunday School versus

Anti-Sunday School issue. The Churches

of Christ were no exception. In an article he titled,

"A Muddled Movement," brother Carl Ketcherside noted the fierce

animosity that had developed between the two perspectives and practices in the Churches of Christ.

"Neither regards the other as in its 'fellowship;' both brand and

stigmatize each other as 'unfaithful' and 'disloyal,' each using its party

prejudices as the criterion of faith and loyalty to the Lord Jesus" (Mission Messenger, vol.

22, no. 6, June, 1960). "Each looks upon its own party as being the one

holy, catholic church, and apostolic church of God on earth, regarding the

others as apostates"

(ibid).

- In the Churches of

Christ most of the Anti-Sunday School congregations have also divided

among themselves over an issue regarding the cup in the Lord's

Supper. Many of them are One Cup advocates, regarding those who

use "multiple cups" as apostates who are bound for

hell. These factions have further divided among themselves regarding when

and how the bread should be broken during the Lord's Supper. Some

feel it should be broken before the prayer by the one administering the

meal, others feel each person should break off their own piece. Thus, we

have the "Bread-breakers" versus the "Bread-pinchers."

We have the "Wine Only" versus the "Grape Juice Only"

groups. The "One Cup" versus the "Multiple Cup"

groups. And on and on and on ... ad infinitum. With every newly

perceived particular of the Pattern a new party is

formed, with each splinter group claiming that it, and it

alone, is the "one true church" on the face of the earth,

with all others who differ with them being godless apostates.

Dr. Dallas Burdette, a devoted brother in Christ, and also one of the

early subscribers to and supporters of my Reflections ministry, has written a fabulous

in-depth history and examination of this whole issue. It is titled -- A Brief History of the One-Cup and

Non-Sunday School Movement. I would strongly urge everyone

to go to his web site and read this study. You will be greatly enlightened. The

URL for his web site is -- www.freedominchrist.net

-- When you get to his web page, click on "Sermons and Essays" to

find this study. His background was in

that movement, so he speaks from personal experience in his marvelous essay! I

also want to thank Dallas for including my Reflections web site in his list of

"Online Resources" under the category "Outreach Ministries for

Unity."

The pioneers of the Stone-Campbell

Movement were largely opposed to the Sunday School, at least

during the early years, because they believed there was great potential for

sectarian abuse and misuse of these institutions. As he reflected back to the

apostolic church, Alexander Campbell observed, "Their churches were not

fractured into missionary societies, Bible societies, and education societies;

nor did they dream of organizing such in the world. ... They knew nothing of

the hobbies of modern times" (The

Christian Baptist, January, 1827). Campbell had earlier

characterized Sunday Schools as "a sort of recruiting establishment to

fill up the ranks of those sects which take the lead in them" (The Christian Baptist, August,

1824). "If children are taught to read in a Sunday school, their pockets

must be filled with religious tracts, the object of which is either directly or

indirectly to bring them under the domination of some creed or sect" (ibid).

- In fairness to Alexander

Campbell, however, it should be pointed out that years later he had come

to a much different conviction regarding these Sunday Schools. In 1847 he

wrote, "Next to the Bible Society, the Sunday School institution

stands preeminently deserving the attention and co-operation of all good

men" (The Millennial Harbinger, April, 1847). He went on to

explain that his previous concern with the institution was simply over

"the sectarian abuse" of the system, when various groups and

factions sought to use the Sunday School for indoctrinating their youth in

their particular party positions.

"At the beginning of the twentieth century Churches of Christ

experienced sharp disagreements over the legitimacy of Sunday Schools,

reflecting attitudes from the Stone-Campbell Movement's earliest leaders. Many

congregations began to incorporate classes based on age into their programs.

The most conservative restorationists in Churches of Christ objected to the Sunday

School because it was not authorized by Scripture. Others opposed it because,

as conducted by other religious bodies, it was an extracongregational

organization with its own officers and governance. The fact that women often

taught the classes was yet another point of contention for some members.

Several hundred non-Bible-class congregations had separated from mainstream Churches of Christ by the

1920s. These churches emphasize the responsibility of parents to teach their

own children and the corporate nature of instruction in the church. The

majority of Churches of

Christ, however, accepted the Sunday School as an integral

part of their educational ministry" (The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement,

p. 296).

As just noted, there were some in the Churches of Christ (as well as other groups)

who took exception to the idea of having a Sunday School for the simple reason

-- "You can't find it in the Bible!" This, of course, is the notion

of Patternism.

If one can't show "book, chapter and verse" where the early church

had a Sunday School, then we

can't have a Sunday School. One of the most visible and vocal of these

Anti-Sunday School advocates was Dr. George Averill Trott (1855-1930), who for

a time served as one of the early editors of the Firm Foundation

periodical. Early in the 20th century a battle of journal editorials was waged

over this issue. Not only the Firm

Foundation, but also the Gospel Advocate got involved in this

struggle. For example, J.T. Showalter wrote the following: "Whenever any

man proves the Sunday school to be of divine authority, he can prove missionary

societies to be of divine authority. By all rules of logic, he that 'would the

one retain, must to the other cling.' I emphatically deny that there is any

divine authority for Sunday schools, either by precept or precedent, hint or allusion

... In all the writings of the New Testament there is not one word that even

squints in that direction" (Gospel

Advocate, April, 1910).

The strict patternists believe that if something can't be found

specifically mentioned in the NT writings (a Sunday School, for example), then

for men to practice such is SIN. This is the old "law of silence" or

"law of exclusion" argument of the CENI (command, example, necessary inference)

advocates. Their view is that the silence of the Scriptures is prohibitive (although

even they themselves are grossly inconsistent in the application of this

interpretive rule). In 1928, the proponents of the Anti-Sunday School position,

as well as the One-Cup position (these two positions are almost always found

together in Churches of

Christ), established their own publication. It was called --

Old Paths Advocate -- and is still

being published today.

These legalistic patternists, as a rule, have tended to be very rigid in

their resolve that ALL of those who differ with them on these issues are LOST.

Indeed, when their own

members begin to raise questions, or to suggest another perspective, they are

quickly and decisively cast from the "loyal church." We all saw this

happen very dramatically with the One-Cup brother in Texas who was recently

fired for daring to suggest an expanded view of God's grace! They are typically

extremely intolerant of any view other than their own, although, praise God, we

are seeing some of their leaders (some of whom are subscribers to these Reflections) begin to

move away from this rigid intolerance, and they have actually begun to become

increasingly grace-centered and accepting of others.

- Don L. King, who serves as

the publisher of Old Paths Advocate, clearly conveyed his belief

that the Sunday School issue was indeed a salvation issue. Notice

the following from one of his editorials -- "Is it wrong, sinful to

use more than one cup? Answer: yes, because more than one cup violates the

example given in Scripture; it violates the command for

us to do as Jesus did. ... Listen, brethren: we believe it is wrong to use

more than one cup. We believe people are going to be lost for

using more than one cup. Surely, we believe that! If people are not going

to be lost for using more than one, then let's give up the fight and

heal the division. .... What about Bible Classes? Is it right to divide

the public assembly into classes for the purpose of teaching and allow

women to teach? ... The pattern is always an undivided

assembly with one man at a time doing the teaching" (Old Paths

Advocate, September, 1995).

Conclusion

The purpose of this Reflections

has not been to take sides in this issue either one way or the other, but

merely to present a brief history of the Sunday School movement, and to make

note of those who both approved and opposed it. I am personally willing to

regard as "brethren" those on both sides of the debate. For me personally the whole

Sunday School issue is a NON-issue.

I presently serve in a congregation that has a Sunday School; I could just as easily

serve in one that does not.

What does

concern me, however, is when brethren fuss and fight over such matters, and in

the process fragment

the One Body of our Lord Jesus Christ. Disciples of Christ have been engaging

in dissension for too long, and the only visible result is a divided church.

The Family of God has been fractured into scores of feuding factions, each

claiming to be the "one true church" on the face of the earth. This

is nothing but abominable arrogance, and many will have much to answer for when

they stand one day before the Father. When we all appear before the Throne it

will matter little whether we used one cup or many; what will matter is whether

we surrounded that table united

as One Body. It will matter little on that day whether we

had a Sunday School or not; what will matter is whether we taught our children

to love one another. Brethren, as we look at our history, we

ought to be ashamed of ourselves!! Our behavior is blasphemous!! May God open

our eyes to our condition before it is too late!! “

****************************************************************************************************

Conclusion

Let me ask a question. Are the Bible Classes from God, or from Men. Jesus asked this question about the baptism

of John. We know today, John’s baptism

is from God. If the classes are from

God then let us all have them. But it

seems to me they are from men. As has

been stated they were not in the Church of the 1st century. If we are doing things that were not in the

church of the 1st century, then we are no longer practicing

restoration. If we say we speak where

the bible speaks and are silent where the bible is silent, then we need to try

doing just that, or we are hypocrites .

Show me the classes in scripture and I will join the crowd. Now let me say that I do not hate my fellow

“Class” brethren, the “one container” brethren nor all the 'brethren' of the

denominations (Baptist and all). I have

come to know from God’s word that I cannot hate any, and I am to treat each man

with respect. This does not mean that I

am to join them in their folly. I

understand where he is coming from in the reflections,

but I must disagree with his conclusion.

We must teach what we know and understand as the truth. We must back up our teachings with the word

of God. The atheist teaches to love one

another. Those who believe in evolution

teach tolerance, acceptance, and love of their fellow man. I like what Paul said when he wrote “let

your moderation be known to all men”. I

think that a little moderation, understanding and love would help us in our

endeavor to teach our brethren in error.

In fact I have more respect for those who say let us turn to the Bible

rather than those who say it does not matter, let’s all just get along. The one who is contending for something

which is not found in scripture is the one who causes division in our Lord’s

Church. They are not allowing Christ to

be the head. We must have scripture to

back up what we practice, teach and do, or we are no different from any

denomination.

Lindeal Greer

Friday, March 10, 2006